Been a bit dead around here of late. I do have a science camp comic on the backburner that involves Labubu(s). I don’t know what the proper plural is and I’m sure if I asked the kids I have this afternoon their opinion they’d go with the English-speaker’s tendency to pluralize with ‘s’ if uncertain.

I mentioned this in an earlier post: I’m going back to school! At 30-or-40 years old and already having a doctorate. I need a couple of course credits for a license and one of them is a 101-level class in my Ph.D. subject. Yes, really. The license requirements are pedantic and literal to that point; this has much to do with guild protectionism of a lucrative post and the massive exodus of research scientists into clinical science, given the disemboweling of government/academic research and the dismal state of the biotech industry. But the second class (hematology) is taking more time than I anticipated, given that I insist upon reading the textbook chapters whole and my experience vis-a-vis blood is largely the immune system. Competition for these clinical positions is cutthroat and I’ve got to prove this old dog can still learn new tricks, or, at the very least, indicate that my dismal publication record is not a result of a dismal drive or dismal intellect.

Perhaps you seek too much

Bit of my analogue fetishism/return to notebook the past few years–I’m taking notes by hand, and I have to admit retention is far better than when I just download the lecture powerpoint or even type notes. The tenor of the past few years of my life is one of regret, of wishing-to-do-over–so looking back at my undergrad and grad years and wishing I had (a) done the reading more diligently and (b) taken detailed hand notes. I had been hit by a combination of gifted-kid arrogance and depression. I felt in a weird way that reading the text and taking notes would be cheating–that I should be smart enough to remember stuff told to me once, that I should not be that pedantic apple-polishing student who tries very hard but isn’t all that naturally bright. Looking up examples is cheating; I should be bright enough to extrapolate everything I need know from a few basic rules. It’s all bullshit, of course–I maintain the honors students are the students who lie about how much they study by understating, or they were in my day–but my younger self was disgusted by the idea of being too lock-step with the system and, perhaps most damning, was rewarded for this behavior with good grades and scholarships. I wanted to be so damn naturally smart that I could not-try and be valedictorian. I also had a Hesse-esque fixation on being no-one’s acolyte or student but my own that carried over well into adulthood. I wanted to be the Siddhartha who rejected the tutelage of the Buddha to find his own truth, much as he respected the Buddha’s teachings, the Max Demian who kept his own moral council.

Might I be in a better position now if I had knuckled down that first year of graduate school–sure. I put all my time and reading into my lab rotations and neglected my classes, and that was reflected in my grades, which impacted my lab rotations when it was time to get a permanent lab. I was frequently at one lab until 1 AM. But that lab (that liked me most) had taken me as a rotation student on the understanding that I would have to secure my own funding to stay with them–and I didn’t, not for lack of trying. I am stupefied meditating on how different my career might look how had I gotten that damn NSF grant, or something. I ended up in a solid enough lab but to make a long story short our off-campus collaborators told me two weeks after I defended that the data upon which I had based my dissertation–and two substantial first-author papers I was waiting for other-author comments on–was faulty, in such a way as to invalidate the entire premise. I was allowed to graduate because I had defended correctly what I had been given in good faith. But, those papers never happened–the PI of the other lab was caring for his wife on hospice and the PI of my own lab had his own age-related issues. I should have been more of an asshole and leaned hard on them but I can’t bring myself to do that to kind old men. It is utterly against my nature to impose upon people, because I hate it so much when people impose upon me, and I treat others as I wish to be treated.

And here I am.

About what you know

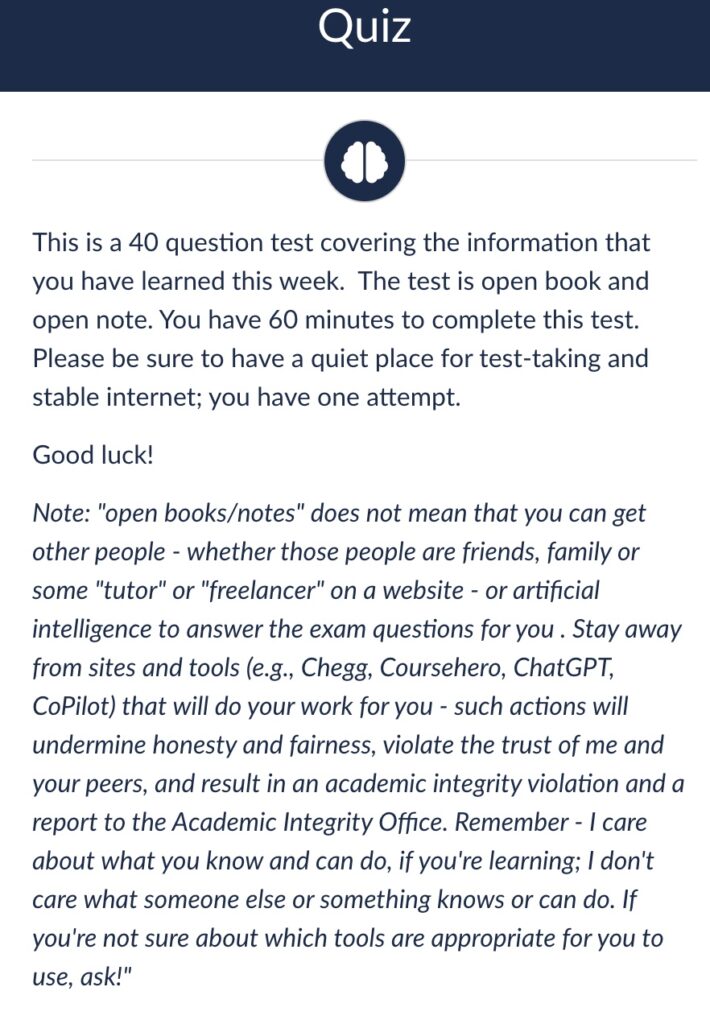

“Note: “open books/notes” does not mean that you can get other people – whether those people are friends, family or some “tutor” or “freelancer” on a website – or artificial intelligence to answer the exam questions for you. Stay away from sites and tools (e.g. Chegg, Coursehero, ChatGPT, CoPilot) that will do your work for you – such actions will undermine honesty and fairness, violate the trust of me your peers, and result in an academic integrity violation and a report to the Academic Integrity Office. Remember – I care about what you know and can do, if you’re learning; I don’t care what someone else or something knows or can do.”

I am so glad I got my Ph.D. before ChatGPT and the other generative AI became prevalent. The date lends a credibility to it. I am also glad I am not teaching remotely in this brave new world because this disclaimer–really, this entreaty–bleeds with desperation that comes of only being able to tell people not to cheat in their own best interest because–please. Just please don’t, else the spirit and credibility of academic accreditation is gone. As an somebody who wanted to be an academic or a post-secondary instructor I understand the desperation, the same way I sometimes wonder how set I’d be were reading and writing still marketable, unique Skills.

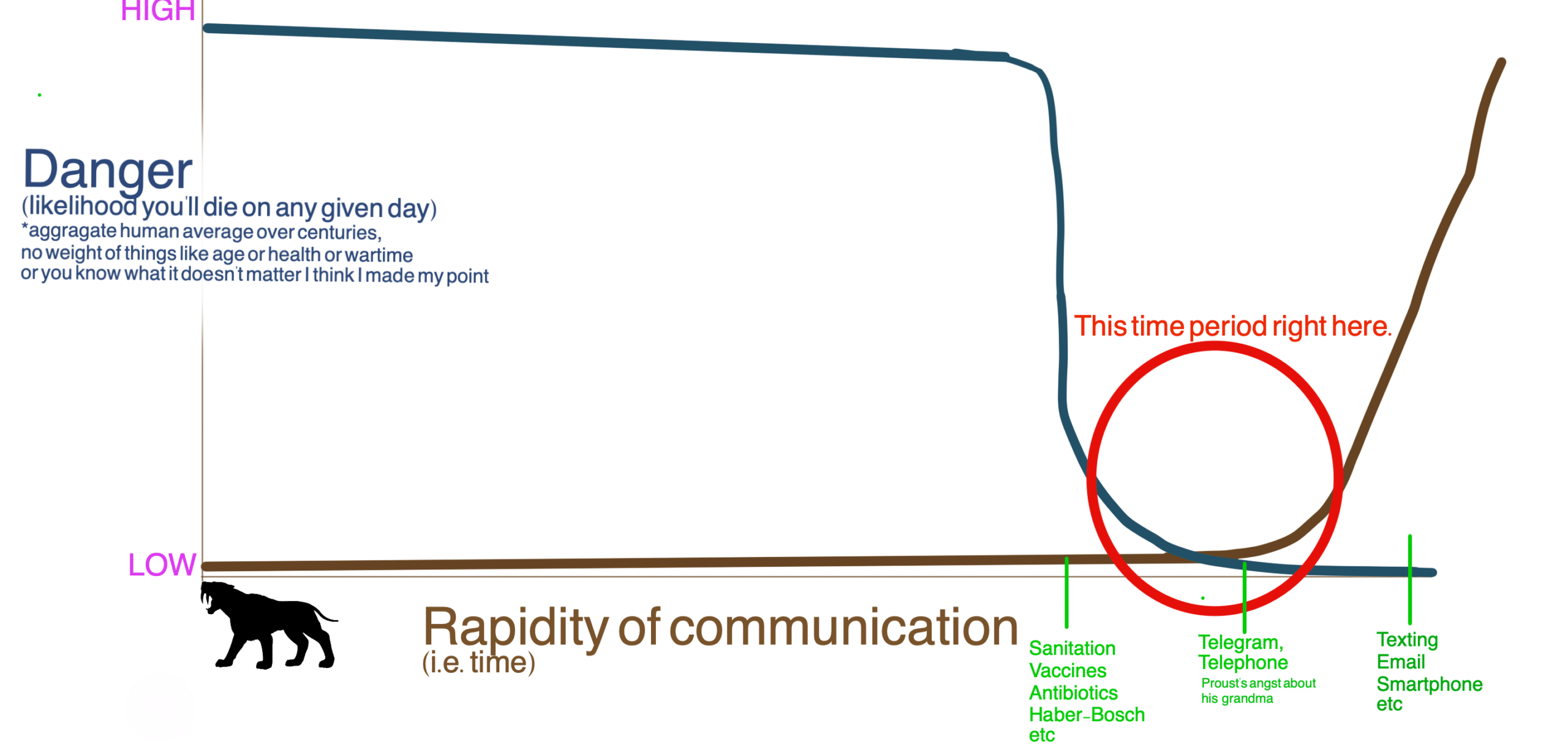

I am a scholar – maybe not so far removed from Buster Bluth as I would like to think, the only thing separating us being that I decided upon a concentration and he had the family largess to be an eternal student.* I’m primarily a knowledge-peddler, a thinker, responding to crisis or shock with paralysis and thinking. Perhaps my kind is ultimately of as little usefulness as a farrier in the age of the automobile, where horses are a novelty and one only needs so many farriers, a very rare lucky few to serve what is an elaborate expensive hobby and not a social need. One can argue whether or not this is intrinsically a bad thing or a loss for society but either way I’m kind of fucked, aren’t I.

You’d be one of the bright ones

That is the message I got growing up in the 90s – I was so intrinsically bright, so intrinsically chosen, that a good life and a fulfilling career were all but guaranteed, and all I had to do was not fuck it up too badly.

That’s another thing that’s difficult to come to terms with, the point where all this intellectual pride intersects with a very American-Protestant pride in being The One Who Rises Above, the cream of the crop, the bright ones who earn a degree of comfort and stability in life. There’s something of the Calvinist pride in being “chosen” to be endowed with natural gifts, that pride in what-one-is and not what-one-earned that is an odd and striking counterpoint to the ‘you must earn everything’ ethos that is the face of that Protestant work ethic. I maintain New Calvinism** appeals in this day of the shattered myth of meritocracy (or the ‘fuck you, I got mine’ era) because it gives realization of this painful truth, at the very least, the aura of stoicism, of clear-minded clear-seeing grit. Like Pa Ingalls letting his family starve before he lowers himself to accepting charity, and that being seen as admirable, American. “Play the hand you’re dealt” and don’t complain, but still be proud of being dealt a good hand. Pride in acceptance of one’s lot. “God did not choose me to deserve much in this life.”

I do not believe you have to be exceptional to have a good quality of life. And yet as the haves and have-nots diverge further, as the middle is hollowed out and the have-nots reach such a majority that the K-shaped wealth curve becomes very bottom-heavy indeed, I still find myself feeling this economic uncertainty and precarity is my fault. I wasn’t one of the Bright Ones after all.

——–

*I also think Lucille is hilarious but I could not actually put up with her in person, let alone live with her, let alone have an incestuous pseudo-marriage with her in which she is in a position of authority over me.

**Consisting mostly of those “extreme” youth churches with a grunge-by-way-of-industrial aesthetic stuck back in 2002 with the billboards all over I-10 that multiply east of LA proper.